Let’s Use Procedure Pointers in Object-Oriented Fortran

Author: Amasaki Shinobu (雨崎しのぶ)

Twitter: @amasaki203

Posted on: 2023-08-28 JST Updated on: 2024-0722

Abstract

This article will cover an implementation of “callback” with procedure pointers in modern Fortran. This allows us to write initial and boundary conditions on numerical computation simply.

Contents

- Introduction

- Preliminary Understanding

- Usage of Procedure Pointers

- Modules and Program written in OOP

- Compilation and Execution

- Conclusion

- Appendixes

Introduction

In classical Fortran, programmers write their code using the procedural programming paradigm. On the other hand, in modern Fortran, the Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) paradigm and procedure pointers are supported starting from Fortran 2003 standards.

In the field of numerical computation, utilizing OOP streamlines source code management, simplifies code modification, and reduces human errors, even though there is some overhead.

This article explores practical implementations of callbacks using procedure pointers in modern Fortran’s object-oriented paradigm.

Preliminary Understanding

In Fortran, object-oriented programming is achieved by

declaring subroutines and functions below the

contains statement of a derived type, associating

them with that type. This is referred to as type-bound

procedures. Type-bound procedures, similar to regular

procedures, can also accept procedure pointers

as arguments.

Procedure pointers are pointers that refer to procedures,

allowing for the switching of procedures and invocation of

associated procedures using the pointer’s names. In Fortran,

they are defined using explicit interface blocks

and procedure statements for procedures. For

exmple:

interface

function f(x) result(res)

real, intent(in) :: x

real :: res

end function f

end interface

procedure(f), pointer :: fptrwhere between the interface and

end interface keywords, there is a section known

as an ‘interface block’, and interface f is then

specified within the parentheses of the procedure

statement.

By using them, it becomes possible to create callbacks, allowing for concise handling of initial and boundary conditions in Fortran numerical computation codes. This further amplifies the ease of changes brought by OOP, enhancing the overall convenience.

In the following, we will examine the simplicity of performing assignments to array components within a derived type via a procedure pointer.

Usage of Procedure Pointers

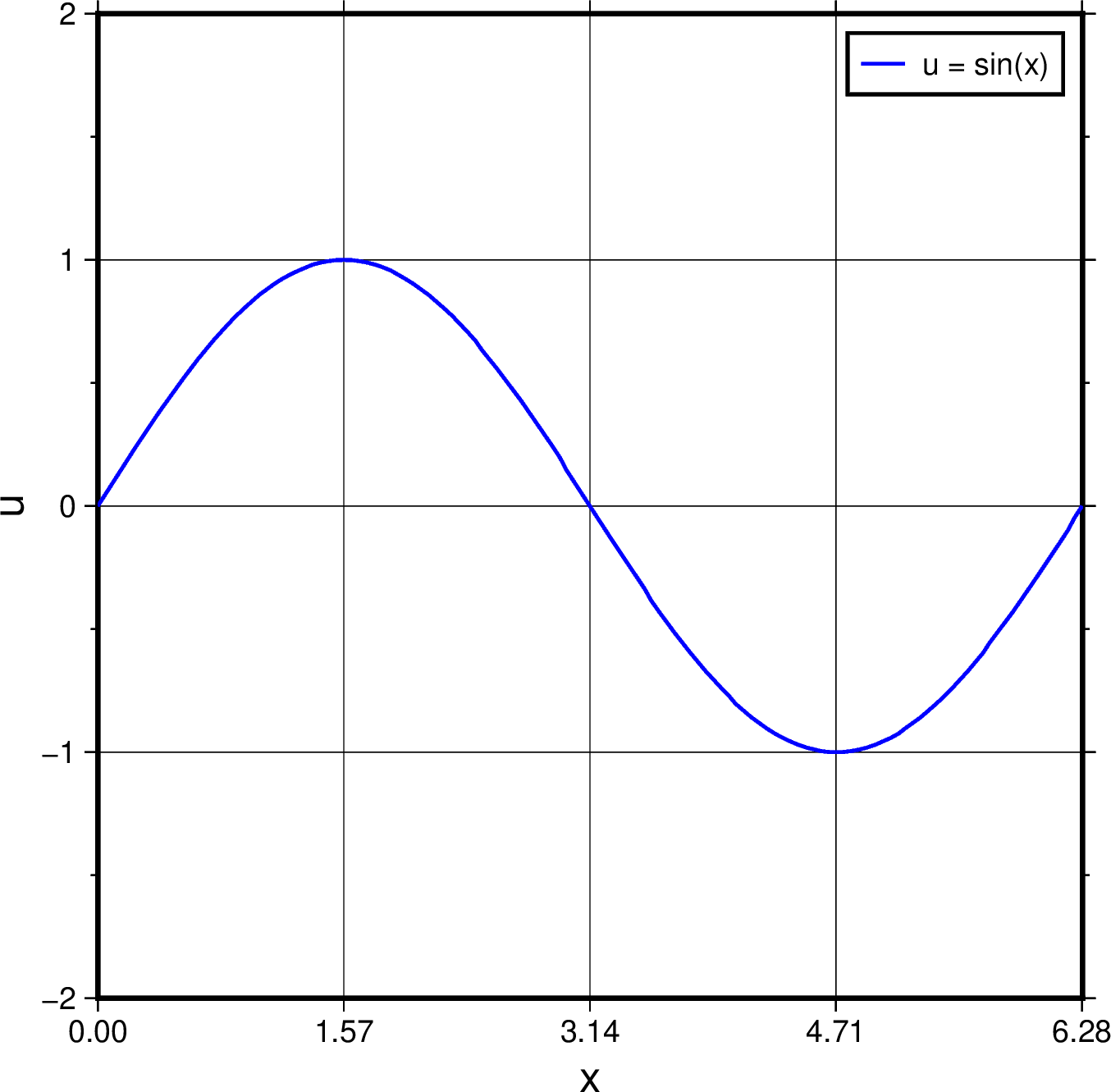

For example, let’s consider providing a basic sine function as the array of the initial values.

To provide this array of initial values, we can achieve it by utilizing the module implemented with OOP, as explained in the following section. This can be accomplished by executing the following statement:

fptr => dsin

call u%allocate()

call u%initialize(fptr)In the first line, fptr is associated with the

intrinsic function dsin, which is the double

precision sine function. In the second line, the statement

calls the type-bound procedure allocate() of the

derived type u. Finally, in the third line, the

type-bound procedure initialize(fptr) is invoked

with the fptr as its actual argument.

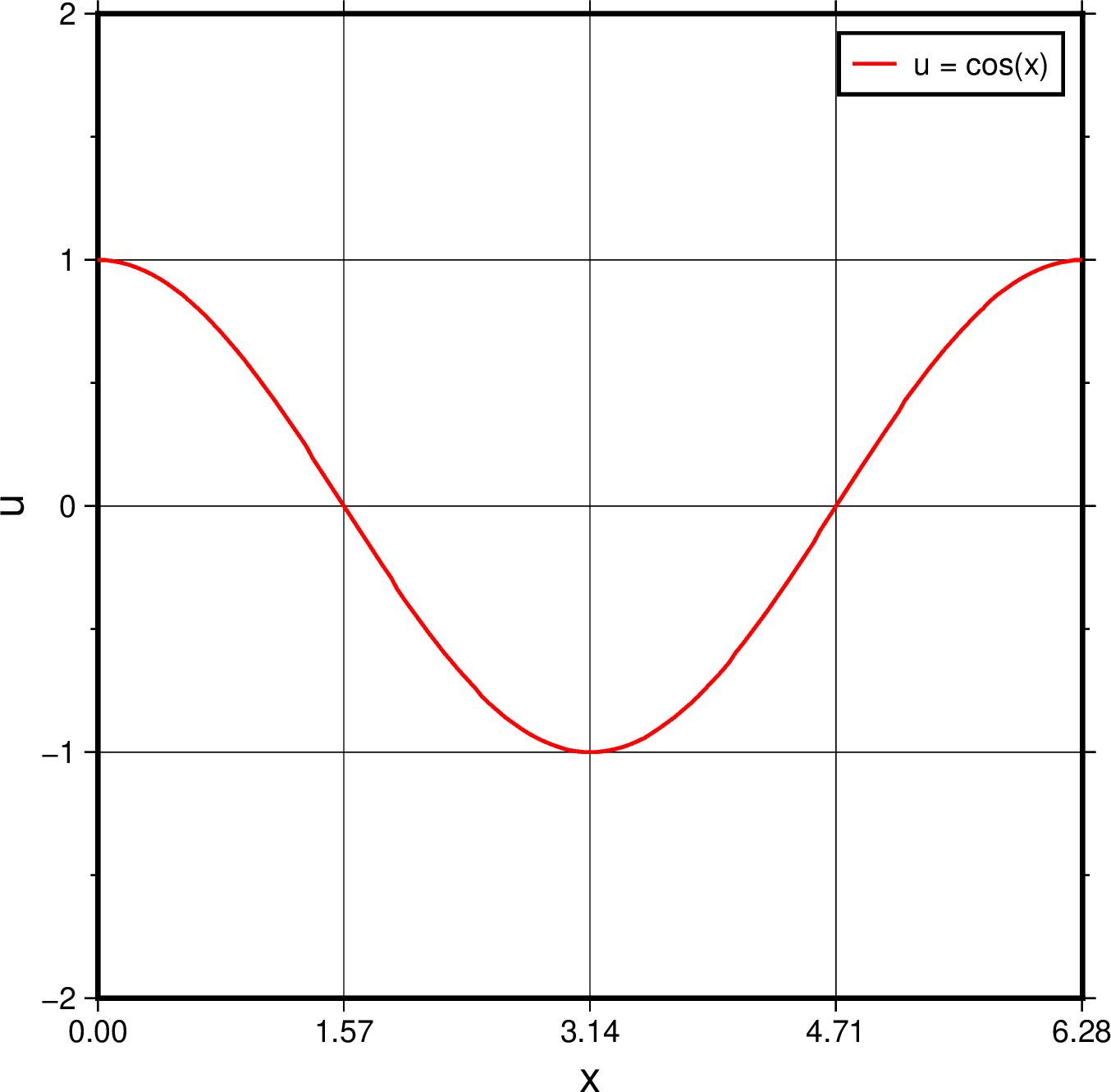

If we want to switch to a cosine function, we can achieve this by simply changing the function that the pointer refers to, as follows:

fptr => dcos

call u%initialize(fptr)where dcos is the intrinsic function that

returns the value of the double precision cosine function.

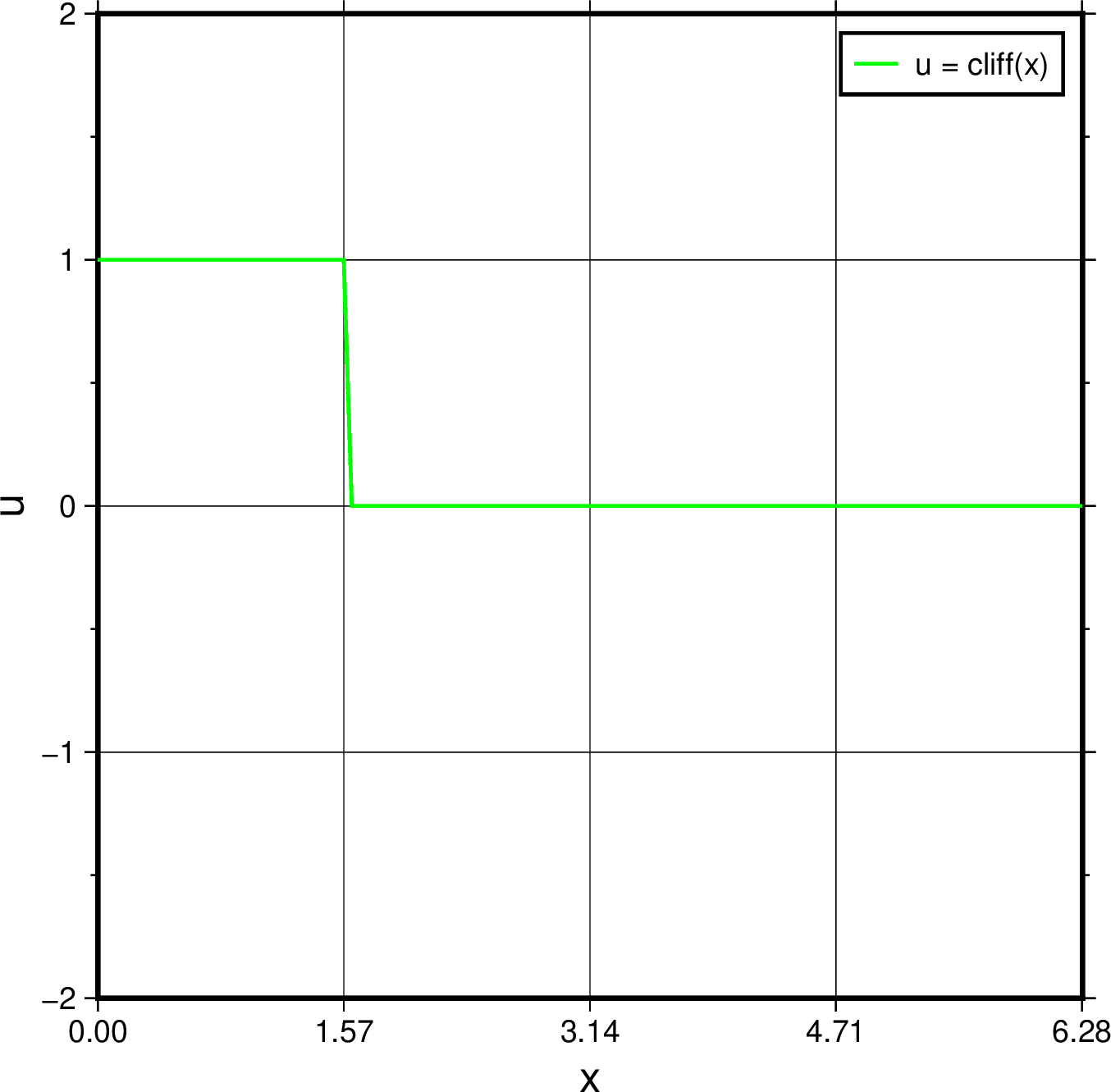

Procedure pointers can refer to procedures defined by users.

...

fptr => cliff ! fptr refers to the user-defined procedure 'cliff'.

call u%allocate()

call u%initialize(fptr)

call data_output()

contains

! Internal procedure 'cliff'

function cliff(x)

implicit none

real(real64) :: cliff

real(real64), intent(in) :: x

real(real64), parameter :: pi_halved = acos(-1d0)/2d0

! staircase function

if (x <= pi_halved ) then

cliff = 1d0 ! for less than or equal to π/2,

else

cliff = 0d0 ! otherwise.

end if

end function cliff

...Plotting this, we obtain the following a graph of the function.

From above examples, it becomes evident that using a procedure pointer as an argument for type-bound procedures simplifies code writing and enhances flexibility for initializing arrays.

In the next section, we will discuss modules written in an object-oriented manner that achieve these functionalities.

Modules and Program written in OOP

Here, for simplicity, let’s think about an application composed of the following three Fortran codes:

module kernelperforms initialization operation on arrays,module class_Variabledefines the derived typeVariable, andprogram mainis the main program.

The entire three source code files are available on the page of GitHub.

module kernel

This module includes the definition of constant parameters

and a callback process. The initialize subroutine,

which initializes an array using the passed function pointer as

an argument, is implemented as a module procedure.

module kernel

use :: iso_fortran_env, only: real64

implicit none

private

public :: initialize

! Number of discretized points along the computing region

integer, parameter, public :: nx = 2**8+1

! Value of the mathematical constant π (pi)

real(real64), parameter, public :: PI = acos(-1d0)

! Length of the computing region [0, L]

real(real64), parameter, public :: L = 2*PI

! Interval between adjacent points

real(real64), parameter, public :: dx = L/dble(nx-1)

contains

! Callback: Define a subroutine to initialize

! an array using a function pointer.

subroutine initialize(array, fp)

use, intrinsic :: iso_fortran_env, only: real64

implicit none

real(real64), intent(out) :: array(:)

! Declare the procedure pointer for the function.

pointer :: fp

! Interface block for the function pointer 'fp'.

interface

function fp(x) result(res)

use, intrinsic :: iso_fortran_env, only: real64

real(real64), intent(in) :: x

real(real64) :: res

end function fp

end interface

integer :: i

real(real64) :: x

!---- End of specification statements for 'initialize' -----!

!---- Begining executable statements of 'initialize'-----!

! Loop through indices 1 to nx of the array.

do i = 1, nx

! Compute x-axis value

x = dble(i-1)*dx

! Pass the actual argument x to the procedure pointer and

! assign the result to array(i).

array(i) = fp(x)

end do

end subroutine initialize

end module kernelWhen we write the interface block in the

module’s specification statements section, we can declare

procedure pointers such as the following statement in internal

subprogram section:

procedure(fp), pointer :: fptrIn this case, variable names for function pointers cannot be

used if they conflict with names declared in the

interface block.

module class_Variable

This module defines the derived type Variable

with the component array value(:) and the three

type-bound procedures: allocate,

initialize, and deallocate.

These procedures perform following processes respectively:

- The

allocatesubroutine allocates the componentvalueasvalue(nx), - The

initializesubroutine takes a procedure pointer as its argument, and passes both its own object’svaluecomponent and the procedure pointer to theinitializesubroutine of thekernelmodule, and - The

deallocatesubroutine deallocates the componentvalue.

module class_Variable

use, intrinsic :: iso_fortran_env

private

public :: Variable

! Define the derived type 'Variable'

type Variable

! An component 'value'

real(real64), allocatable, public :: value(:)

contains

! type-bound procedures

procedure, public, pass :: allocate

procedure, public, pass :: initialize

procedure, public, pass :: deallocate

end type Variable

contains

! Allocate the component of derived type variable 'self'

subroutine allocate(self)

use :: kernel, only:Nx

implicit none

! Declare the variable named 'self' as the class Variable type.

class(Variable), intent(inout) :: self

if (.not. allocated(self%value)) then

allocate(self%value(Nx), source=0d0)

end if

end subroutine allocate

! A wrapper procedure that invokes initialization by passing

! a procedure pointer 'fp' to the 'initialize' procedure of

! 'kernel' module.

subroutine initialize (self, fp)

use, intrinsic :: iso_fortran_env, only: real64

! Make alias for the 'initialize' procedure in the 'kernel' moudle

! named 'kernel_init'.

use :: kernel, only: kernel_init => initialize

implicit none

class(Variable), intent(inout) :: self

pointer :: fp

interface

function fp(x) result(res)

use, intrinsic :: iso_fortran_env, only: real64

real(real64), intent(in) :: x

real(real64) :: res

end function fp

end interface

! Invoke the 'kernel_init' procedure

call kernel_init(self%value, fp)

end subroutine initialize

! Deallocate the component of variable 'self'

subroutine deallocate(self)

implicit none

class(Variable), intent(inout) :: self

if (allocated(self%value)) then

deallocate(self%value)

end if

end subroutine deallocate

end module class_VariableIn the specification statements section of the

initialize, we have to write an

interface block about the procedure pointer of the

dummy argument. As mentioned in the previous section, we can

write an interface blocks in the module’s

declaration section and then declare procedure pointers using

the procedure(fp) statement.

program main

The following code is the main program of this application.

The module kernel and

class_Variable are first imported using the

use statements.

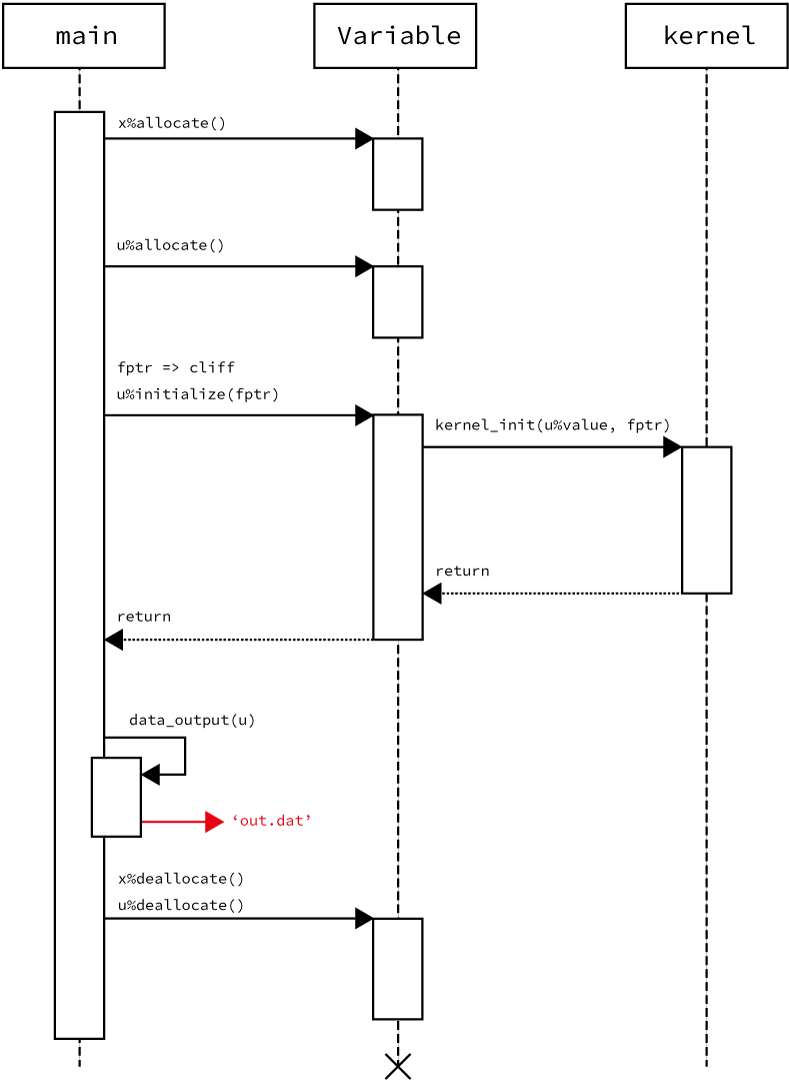

In the execution section:

- Firstly, a Variable type variable

xis created to represent the x-axis coordinates for output. - Next, the procedure pointer

fptris associated with the internal functioncliff. - Then, the type-bound procedures

u%allocate()andu%initialize(fptr)are invoked, allowing the use of the procedure pointer to assign initial values to thevaluecomponent ofu. - Finally, after calling the subroutine

data_outputto output the data, the allocations of components foruandxare deallocated using the type-bound proceduredeallocate.

program main

use :: iso_fortran_env, only:real64

use :: kernel, only: nx, dx

use :: class_Variable, only: Variable

implicit none

! Declare derived type variable u and x.

type(Variable) :: u, x

! Define the interface of the procedure pointer 'fp'

interface

function fp(x)

use, intrinsic :: iso_fortran_env, only: real64

real(real64), intent(in) :: x

real(real64) :: fp

end function fp

end interface

! Declare the procedure pointer variable 'fptr',

! initializing it refers to null().

procedure(fp), pointer :: fptr => null()

integer :: i

! Generate the x-axis coordinate values for data output.

call x%allocate()

do i = 1, nx

x%value(i) = 0d0 + dx*dble(i-1)

end do

call u%allocate()

! Associate the procedure pointer 'fptr' with the internal function 'cliff'.

fptr => cliff

! fptr => dsin

! fptr => dcos

! Invoke the type-bound procedure 'initialize' of the variable 'u'

! of the 'Variable' derived type, passing the procedure pointer 'fptr'

! as an actual argument.

call u%initialize(fptr)

call data_output(u)

! Call the procedure for deallocation.

call u%deallocate()

call x%deallocate()

contains

! User-defined internal procedure 'cliff'

pure function cliff(x)

implicit none

real(real64) :: cliff

real(real64), intent(in) :: x

if (x <= 1.57d0) then

cliff = 1d0

else

cliff = 0d0

end if

end function cliff

! Output data with formatted output.

subroutine data_output(v)

use :: kernel, only: nx

implicit none

type(Variable), intent(in) :: v

integer, save :: uni = 10

integer, save :: count = 1

character(7), save :: filename = 'out.dat'

logical :: isOpened

inquire(file=filename, opened=isOpened)

if (.not. isOpened) then

open(uni, file=filename, form='formatted', &

action='write', status='replace')

end if

write(uni, '(a, i0)') '> -Z', count ! header for GMT6

do i = 1, nx

write(uni, '(e10.3, 1x, e10.3)') x%value(i), v%value(i)

end do

count = count + 1

end subroutine data_output

end program mainSequence diagram

The above application is represented by the following sequence diagram.

Compilation and Execution

Compilation

Compile the code using the GNU Fortran Compiler

gfortran:

% gfortran -c kernel.f90

% gfortran -c class_Variable.f90

% gfortran -c main.f90

% gfortran kernel.o class_Variable.o main.o -o a.outAlternatively, compile with the Intel Fortran Compiler

Classic ifort from the Intel oneAPI HPC

Toolkit:

% source /opt/intel/oneapi/setvars.sh

% ifort -c kernel.f90

% ifort -c class_Variable.f90

% ifort -c main.f90

% ifort kernel.o class_Variable.o main.o -o a.outExecution

Upon running the application, a data file named

out.dat will be generated, completing the

preparations for plotting the aforementioned figures.

% ./a.out

% head -n 10 out.dat

> -Z1

0.000E+00 0.100E+01

0.245E-01 0.100E+01

0.491E-01 0.100E+01

0.736E-01 0.100E+01

0.982E-01 0.100E+01

0.123E+00 0.100E+01

0.147E+00 0.100E+01

0.172E+00 0.100E+01

0.196E+00 0.100E+01Conclusion

We have discussed constructing Fortran programs using object-oriented programming techniques and explored the method of passing procedure pointers for initializing arrays. This approach helps clarify the roles of the main program and modules, making it easier to reuse code effectively.

There is very limited information available in both English and Japanese about Fortran procedure pointers. I hope this article serves as a helpful resource for you to enhance your codes.

Appendixes

Notes

Execution of Fortran programs containing pointers compiled

with the Intel Fortran Compiler might not be as fast, so it’s

recommended to use the -O2 optimization

compilation option whenever possible, unless it causes any

issues.

The figures of the graphs of functions were created using Generic Mapping Tools version 6.4.0. I will include a Bash script for plotting in the following:

#!/bin/bash

### Use GMT6 on Gentoo Linux

type gmt6 > /dev/null

if [[ $? -eq 0 ]]; then

shopt -s expand_aliases

alias gmt='gmt6'

fi

###

proj="X4i"

stem="out"

range="0/6.283/-2/2"

gmt begin $stem png

gmt basemap -J$proj -R$range -Bya1f0.5g1+l"u" -Bxa1.57f1.57g1.57+l"x" -BWeSn

gmt plot out.dat -J$proj -R$range -Cgreen -W1p -Z1 -l"u = cliff(x)"

gmt endTested Environments

The Operating Systems of my machines are Gentoo Linux (kernel version 6.1.31), and compilers’ version are following:

% gfortran --version

GNU Fortran (Gentoo 12.3.1_p20230526 p2) 12.3.1 20230526

Copyright (C) 2022 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software; see the source for copying conditions. There is NO

warranty; not even for MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

% ifort --version

ifort (IFORT) 2021.9.0 20230302

Copyright (C) 1985-2023 Intel Corporation. All rights reserved.